Language is a living thing. It evolves with every conversation, adapts to technological shifts, and absorbs new slang expressions, constantly growing in unexpected directions. One of the most overlooked contributors to this growth? Brands.

Some brand names can take on a life of their own, transcending their commercial origins to become part of everyday vocabulary. Take “escalator” as an example. Originally a trademark coined by the Otis Elevator Company around 1900, it used to refer exclusively to Otis’s own brand of moving staircases. However, as these futuristic devices became ubiquitous, the word was soon generically used to describe any moving staircase, regardless of the manufacturer. Interestingly, it even gave birth to the verb “escalate”, which now applies to a broad range of contexts, ranging from rising tensions to intensifying situations.

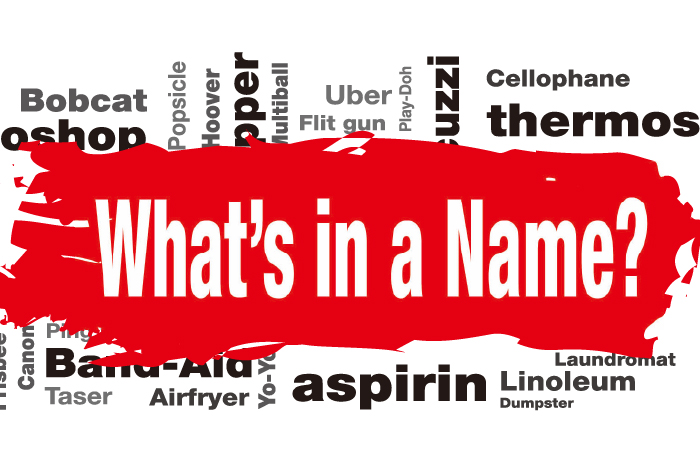

Let’s look at a few more examples. Do you say a vacuum flask or thermos? A separable fastener or zipper? An adhesive bandage or band-aid? A whirlpool bath or jacuzzi? Sticky notes or post-it? You probably use, without a second thought, the latter—which are (or used to be) trademarks—to describe goods or services in a generic way.

Even more intriguing is the phenomenon of brand names turning into verbs. This process—what some call “verbing” and linguists refer to as “denominalisation”—fills gaps in our language, offering a convenient and universally understood shorthand for actions we frequently perform. Expressions like “Just google it” and “It’s photoshopped” illustrate this perfectly. While they might originally refer to using Google and Adobe Photoshop specifically, they are now often used to describe respectively the act of searching online with any search engine and editing photos with any software. As these terms are already embedded in our daily speech, they are often written in lower case.

At first glance, it might seem harmless, or even flattering, for a brand to become part of the lexicon. But for businesses, it can spell disaster. If a trademarked name no longer identifies a specific brand and is instead perceived as an entire category of products or services, it might face what is known as “genericide” and lose legal protection.

One of the most famous cases of genericide is Aspirin, a painkiller developed by Bayer, a German pharmaceutical giant. In the legal case of Bayer Co. v. United Drug Co. in 1921, Bayer lost the exclusive right to use “Aspirin” as a trademark in the United States. The court ruled that the generic status of a trademark would depend on how the general public used the term, rather than how specialists such as chemists and pharmacists perceived it.

To avoid a similar fate, many companies have gone to Herculean lengths to educate the public about the proper use of their trademarks. Xerox, for example, has long fought against its name becoming synonymous with photocopying. A 2003 advertisement made the point in a humorous way, stating: “When you use ‘Xerox’ the way you use ‘aspirin’, we get a headache.” In 2019, the company published a notice in a Manila newspaper to remind the public that Xerox is not a generic name: “As a registered trademark, XEROX is also not a verb or common noun and should therefore not be used to describe copying or copy services in general. So please don’t use the word ‘XEROX’ as another word for ‘copy’.”

Some enterprises have taken it a step further. Velcro released a playful music video titled “Don’t Say Velcro”, in which actors playing lawyers sing about how Velcro is a trademark rather than a generic term for hook and loop fasteners. Similarly, Johnson & Johnson have tweaked its famous jingle from “I’m stuck on Band-Aid” to “I’m stuck on Band-Aid brand” to reinforce the idea that Band-Aid is a brand name, not a descriptive term. Companies discourage the use of plural form for their brand names, favouring “LEGO bricks” over “LEGOs”, for instance, and use distinctive fonts to set their trademarks apart.

Companies pour millions into making their brand a household name and, ironically, spend even more to avoid suffering from their own success. While Juliet tries to tell Romeo that a name is nothing but a name in her famous soliloquy, those in the business world would have said, “A name is everything.”