At the turn of the 21st century, Neil MacGregor, the then director of the British Museum, undertook a formidable task: to recount the million-year-long human odyssey with just 100 objects culled from the museum’s vast collection.

“The whole project is an absurd one, obviously,” MacGregor admitted, “to try to tell a history of the world anyway, let alone in 100 objects.”

Nevertheless, A History of the World in 100 Objects—a series of 15-minute programmes first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2010—became a runaway success, garnering compliments like “perfect radio” and “a broadcasting phenomenon”. Brilliant on air, its lavishly illustrated companion book of the same title is equally mesmerising. As with the radio series, five objects are grouped chronologically under 20 intriguing topics such as “Ancient Pleasures, Modern Spice”, “Inside the Palace: Secrets at Court” and “Meeting the Gods”. From the two-million-year-old stone chopping tool from Olduvai Gorge in Africa to the solar-powered lamp made in China in 2010, these objects collectively weave a rich, coherent narrative of human activity across cultures and time.

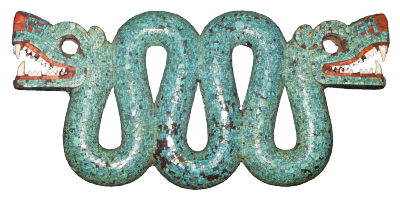

If there is one thing that stands out in the book, it is the breadth of the objects that come from almost every corner of the globe. A few of them, like the Rosetta Stone or the statue of Ramesses II, are iconic and instantly recognisable. Some are less known but no less captivating, such as the mosaic wooden box from a royal tomb in the Sumerian city of Ur in Mesopotamia or the mechanical galleon produced in the late 19th century in the German town of Augsburg. Many are humble relics of everyday life, including pot shards found on a Tanzanian beach, and a ceramic roof tile from a temple in Kyongju, the capital of the Unified Silla Dynasty of Korea.

With an exceptionally well-informed docent, even the most mundane objects can be fascinating. In a clear and eloquent style, MacGregor uses his expertise and storytelling skills to bring these objects to life, shedding light not just on their historical contexts but also on universal themes such as religious tolerance, urbanisation, technological advances and women’s rights. One particularly striking example is a suffragette penny—an ordinary British coin minted in 1903 with the slogan “VOTES FOR WOMEN” hand-stamped over the profile of King Edward VI. In MacGregor’s hands, this small act of defacement offers a window into the long and hard-fought struggle for women’s suffrage in Britain, inviting readers to reflect on the boundaries of civil disobedience and the fight for equality.

The diversity of the objects and MacGregor’s engaging narration contribute to the success of this project, as does his choice of contributors and collaborators. Each vignette features input from experts across various fields—anthropologists, artists, writers, and even lawyers—many of whom share cultural or racial heritage with the objects in question. In his presentation of a brass plaque from Benin City, Nigeria, for example, MacGregor includes commentaries from Nigerian-born sculptor Sokari Douglas Camp and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka. These multiple voices and perspectives add layers of meaning and offer personal reflections on the cultural significance of the objects.

As the title suggests, MacGregor is presenting “a”, not “the”, history of the world. Unlike conventional histories that focus on significant historical figures and events, this book allows objects to speak for the defeated and forgotten. While written records tend to skew towards the victors in wars, conquests and cultural clashes, artefacts left behind by the vanquished inadvertently take on the role of silent witnesses, reminding us of the people and cultures that created them. MacGregor urges us to see how these objects unite us together in our common humanity. He concludes, “Above all, I hope this book has shown that the ‘family of man’ is not an empty metaphor, however dysfunctional that family usually is; that all humanity has the same needs and preoccupations, fears and hopes. Objects force us to the humble recognition that since our ancestors left East Africa to populate the world we have changed very little.”

It is with this broadened perspective that A History of the World in 100 Objects becomes not only a journey into our past but also a meditation on our future. The objects we leave behind today will serve as testaments to our achievements and failures tomorrow, telling our future generations who we are, where we come from, and how much or how little we have learnt from history.