Shortly after being diagnosed with an incurable brain tumour in 2002, British novelist and poet Martin Booth dedicated himself to writing a memoir for his children, who wished to know more about their father’s early life. His last work, Gweilo: A Memoir of a Hong Kong Childhood, is an engaging and intimate account of his memorable days in a city which he would eventually call home.

In June 1952, seven-year-old Booth arrived in Hong Kong with his parents after his father, a supplies clerk attached to the Royal Navy, was offered a three-year posting. At the welcome lunch upon the family’s arrival, the little boy met a naval officer who introduced him to prawns and Coca Cola and, more importantly, gave him a word of advice. “So long as you are in Hong Kong,” said the officer, “whenever someone offers you something to eat, accept it.” Booth duly obliged, accepting not only such weird delicacies as preserved eggs and stir-fried water beetles, but also a culture alien to him.

This sense of acceptance was fostered by his mother, “a humanist at heart who believed no man should lord it over another” in Booth’s words. Unlike many of her fellow expatriates, she was very willing to engage with locals, and took her son to the wilds of the New Territories and outlying islands. Contrary to his vivacious mother who readily embraced the culture and beauty of the place, his bigoted father remained detached and resolutely standoffish, making little effort to understand the city or its people.

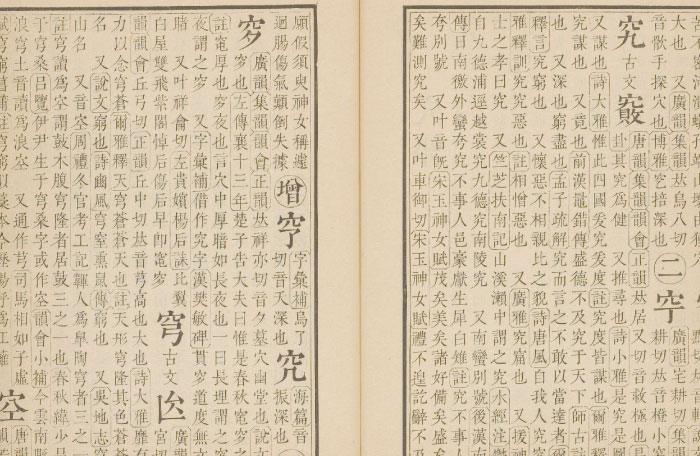

Booth went to Kowloon Junior School, but his real education took place outside the classroom. Since his blonde hair was “considered by the Chinese to be the colour of gold and therefore likely to impart wealth or good fortune”, Booth was able to charm his way through every nook and cranny of the city. He made friends with people from all walks of life, and encountered a colourful array of characters—from Nagasaki Jim, who became a prisoner of war at the fall of Hong Kong in 1941, to the deranged Russian tramp who was dubbed “the Queen of Kowloon”. The streets were his “patch” and “playground”. During a bold adventure in the notorious and lawless Kowloon Walled City, Booth was confronted by a triad gangster called Ho. With great composure, the streetwise kid held his hand out and introduced himself in Cantonese. As unlikely as it might seem, the two became acquaintances. In the following excursions, Booth was given private tours of the enclave and even visited an opium den.

While befriending rickshaw coolies, hotel workers and gang members, the golden boy also attended beach parties and enjoyed afternoon tea at The Peninsula, flitting freely between both worlds. “A good memoir,” asserts literary critic William Zinsser, “is also a work of history, catching a distinctive moment in the life of both a person and a society.” Through the curious eyes of a child, readers can witness the social and geopolitical upheavals of turbulent times, such as the Shek Kip Mei fire, the Korean War and the influx of refugees from Mainland China. Booth’s personal narrative adds depth and tactility to the events he recalled, enabling readers to appreciate both the larger historical context and the cultural milieu that shaped Hong Kong in the 1950s. His love and fascination for Hong Kong is palpable. And his description is so vivid and powerful that the spirit of the city comes across on every single page.

The book closes with the Booths boarding the ship back to England, but their story did not end there. Four years later when Booth’s father accepted a new job, the family returned and stayed until Booth completed his secondary education. His formative years in the city left an indelible imprint on his heart and coloured much of his subsequent works. His first best-seller Hiroshima Joe is inarguably based on the story of Nagasaki Jim. Not only are a few of his novels set in Hong Kong, his non-fiction books Opium: A History and The Dragon Syndicates: The Global Phenomenon of the Triads are also apparently inspired by his adventurous experiences in the Walled City. It seems home is more than a geographical location. It is a place associated with the most special memories of our lives and the connections we have made with others. “If the truth be told,” Booth writes in the Author’s Note of Gweilo, “I have never really left Hong Kong.”

Photo credit:(top) Lands Department, HKSARG; (bottom left) Martin Booth / Gweilo: A Memoir of a Hong Kong Childhood